Hand Battery

Your skin and two different metals create a battery.

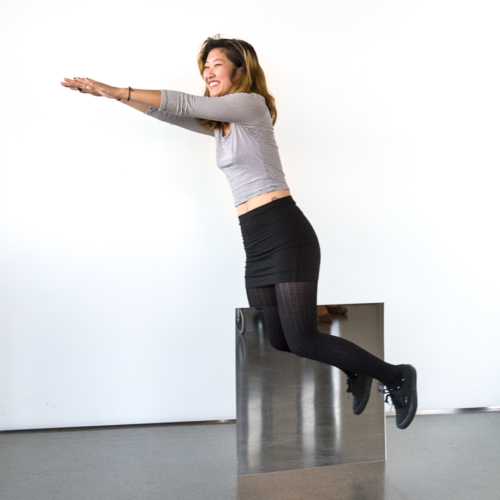

When you place your hands on metal plates, you and the plates form a battery.

The current generated by Hand Battery is directly related to the contact surface area between your hands and the plates. You can see how much this changes by pressing down lightly versus pressing hard.

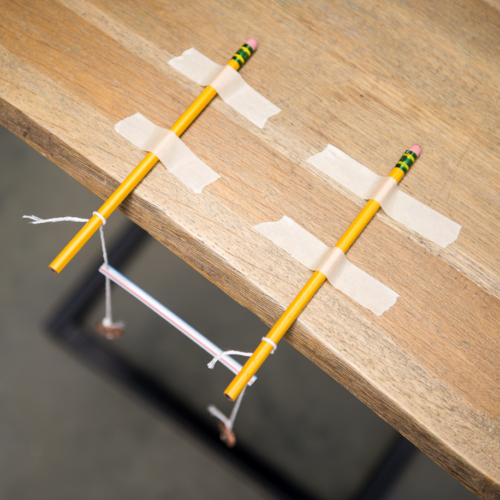

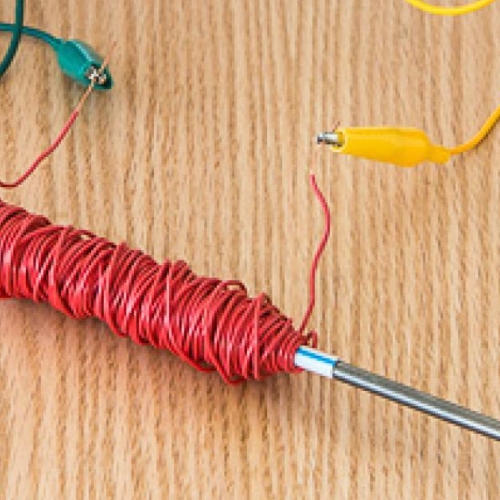

- An aluminum plate (or aluminum foil) and a copper plate, each about the size of your hand

- Flat wood surface or nonmetallic surface

- Two wires with alligator clips at both ends

- A multimeter (digital or analog—inexpensive models are available online)

- Optional: other metal plates

- Place both metal plates on a piece of wood or other nonmetallic surface.

- Using the clip leads, connect one plate to one of the multimeter’s test probes and connect the other plate to the other probe. At this point it doesn’t matter which plate attaches to which probe.

- Set the multimeter to measure current in milliamps.

Eine Hand auf jede Platte legen. Das Messgerät sollte einen Messwert anzeigen. Wenn es einen negativen Strom anzeigt, vertauscht die Anschlüsse, indem ihr den Messfühler, der an die Kupferplatte angeschlossen ist, an die Aluminiumplatte anschliesst und umgekehrt. Zeigt das Messgerät keinen Strom an, überprüft die Anschlüsse und die Verkabelung. Sollte immer noch kein Strom fliessen, die Platten mit Stahlwolle reinigen, um Oxidationsspuren zu beseitigen.

Versucht, fester auf die Platten zu drücken. Befeuchtet eure Hände und versucht es noch einmal.

Schaltet das Multimeter auf Spannungsmessung und wiederholt die obigen Versuche.

Dann legt eine Person eine Hand auf die Kupferplatte und die zweite Person eine Hand auf die Aluminiumplatte, während sich beide Personen an den freien Händen fassen.

Most batteries use two different materials and an electrolyte solution to create an imbalance of charge and thus a voltage. When the terminals of the battery are connected with a wire, this voltage produces a current.

In this Snack, the thin film of sweat on your hands acts like an electrolyte solution and reacts with the copper and aluminum plates. When you touch the copper plate, a reaction happens that uses electrons. When you touch the aluminum plate, a reaction happens that releases electrons.

This difference in charge between the two plates creates a flow of electrical charge, or electrical current. Because electrons can move freely through metals, the excess electrons on the aluminum plate flow through the meter on their way to the copper plate. In addition, negative electrons move through your body from the hand touching the copper to the hand touching the aluminum. As long as the reactions continue, the charges will continue to flow and the meter will show a small current.

Your body resists the flow of current. Most of this resistance is in your skin. By wetting your skin you can decrease your resistance and increase the current through the meter. Since two people holding hands have more resistance than one person, the flow of current should be less. If you like, you can use the multimeter to measure resistance directly in these situations.

You can use other pairs of different metals in a circuit to produce a current. The success you have using various metals will depend on a metal’s electrode potential, that is, its ability to gain or lose charges. Try various metals to see which produces the highest current reading. An electromotive series table shows the electrode potentials of metals and allows you to predict which metals will work well in making a hand battery.

You can sometimes get a small current even between two plates made of the same metal. Each plate has a slightly different coating of oxides, salts, and oils on its surface. These coatings create slight differences in the surfaces of the metals, and these differences can produce an electrical current.

The slightly painful sensation of a fork tine touching a metal filling, the process of plating metals, sacrificial anodes used to preserve ship hulls and iron bridges, potato clocks, and dielectric unions to prevent deterioration of copper and iron plumbing are all everyday examples of metals transferring charges.